An Example of Local Self-Governance in Taliban-Controlled Afghanistan

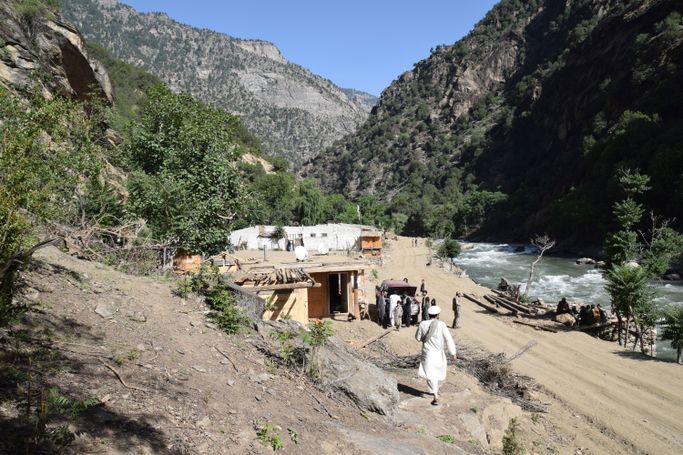

KAMDESH, NURISTAN

May 2022

Since the Taliban returned to power in Afghanistan, they made headlines by re-imposing repressive autocratic laws for which they had become notorious during their previous regime in the 1990s. However, in one remote corner of the country that the current central government as well as bygone ones have barely, if at all, reached, locals govern themselves quasi-democratically — with the acquiescence, and sometimes even participation, of the Taliban.

Local men in Pitigal, the main village of the valley with the same name in Kamdesh District, Nuristan Province, Afghanistan, some of whom belong to the local council that governs the valley (Franz J. Marty, 18th of May 2022)

A Faraway Neglected Place

The eastern Afghan province of Nuristan is, even for Afghan standards, remote. Made-up of steep forested valleys snaking out of the mighty Hindu Kush, the area is so inaccessible that, until the late 19th century, local people had resisted outside influence and remained adherent to an ancient animist religion. Then known as Kafiristan, the Land of the Infidels, the region was only conquered by the armies of the Afghan emir in 1895 who also forcibly converted locals to Islam and renamed the region Nuristan, the Land of Light. Despite this nominal inclusion into the Afghan state, Nuristan has remained and still remains a remote backwater that sees at best minuscule presences of whatever government is in charge in the distant Afghan capital Kabul.

This has not changed with the Taliban’s lightning toppling of the former Afghan Republic last August. Indeed, in Kamdesh the easternmost district of Nuristan, the Taliban’s district

administration, as of May 2022, only counts a few men in an impromptu repaired building that is still slightly dilapidated. The only vehicles they have — important assets in a place where

distances between villages and side valleys can be far — are two Ford Rangers captured from the now defunct police of the Afghan Republic. However, during the visit of the fellow of the Swiss

Institute for Global Affairs (SIGA) to Kamdesh in mid-May 2022, neither of the two Rangers worked properly. Nevertheless, Hezbullah, the Taliban’s deputy district governor for Kamdesh who

hails from one of its side valleys, asserted: «There are no problems and all is fine in Kamdesh.»

The Taliban’s district governor’s office in Kamdesh District, Nuristan Province, Afghanistan (white building in centre) (Franz J. Marty, 14th of May 2022)

To locals, Taliban officials are reportedly more honest. «I went to the district governor with plans to improve a road», one village representative in Kamdesh recounted to the SIGA fellow, «but he said that they [the Taliban] have currently no capacity at all [to implement projects] and told me to directly ask [non-governmental] organisations for help.» Other locals in Kamdesh confirmed this. «The [Taliban] Emirate has itself no money. How should they get anything done?» one man sitting with others on timber beams under a tree asked rhetorically, echoing statements that SIGA also heard from others.

This is no new experience for residents of Kamdesh as the erstwhile Afghan Republic, whose representatives had already been effectively under siege in the district centre for years before the fall of Kamdesh last summer, had also not done much, if anything for locals.

Local Councils & Village Chiefs

In this absence of an effective government, Kamdeshis have stuck to traditional systems of self-governance — during the time of the Afghan Republic and now under the Taliban Emirate. «They have their rulers in Kabul, we rule ourselves here», an old Kamdeshi summed the situation up. «We have done this since kafir [i.e. pre-Islamic] times.»

How this looks in practice, differs slightly from village to village and valley to valley.

In the cluster of settlements that make up the main village of Kamdesh as well as nearby Urmur, people elect village councils by hand raising or paper ballots, as several locals confirmed. These council then, in turn, elect a village chief who acts as main representative as well as mediator and implements decisions of the council. «Such elections take place every spring», a member of the council in Urmur told SIGA. Others added that council members and village chiefs are regularly not re-elected but exchanged.

«Every man above around 17 years old is eligible to vote», Rahimullah, an old man in the main village of Kamdesh further explained. The age threshold is not fixed as the criteria is less the age but the moment when a young man becomes eligible — and obligated — to contribute to community work like maintaining roads, Rahimullah and other locals elaborated.

The main village of Kamdesh, perched high above the Landai Sin valley in Kamdesh District, Nuristan Province, Afghanistan (Franz J. Marty, 12th of August 2021)

In other areas of Kamdesh it is less democratic. «In our valley, the council is elected by all men over 20 years old, but they are more selected without hand raising or other election process», Asluddin, a man in his 30s who has just this year become a member of the council of the Bazgal valley, stated. Abdul Qahar, the man who had been elected this spring to head the whole Saret valley, described something similar. «In the Saret valley, there are six ‘kandi’ [precincts which supply men for community work] each of which sends four representatives to the valley council; these men are selected in discussions within the ‘kandi’ and not in an actual election», he explained.

Nevertheless, and even though women are excluded and that also men are likely not completely free in their voting rights, the described systems amount to some form of direct representation of the general public. This is exemplified by the fact that elected council members in various parts of Kamdesh currently include members of the Taliban as well as former officials of the erstwhile Republic, suggesting that people chose whom they wanted, independent of who is in power.

Richard F. Strand, an anthropological linguist and authority on Nuristan, in particular Kamdesh, confirmed to SIGA that the described system is indeed an old tradition that dates back to the times of Kafiristan. Dr. Max Klimburg, another scholar who has been researching Nuristani culture since decades, then also clarified that similar systems exist in other districts of Nuristan.

«The Taliban have no problems with this [our council system] and are informed about the elections and their results», one man in Kamdesh told SIGA, echoing the statements of others. «It is to their benefit as we solve our problems ourselves and only seldom bother the [Taliban] district officials», he added. That the Taliban are indeed content with this was confirmed by an old man with long white hair, who used to be a Taliban commander and is currently a council member in Saret. This is remarkable as the Taliban have consistently derided democracy as «un-Islamic».

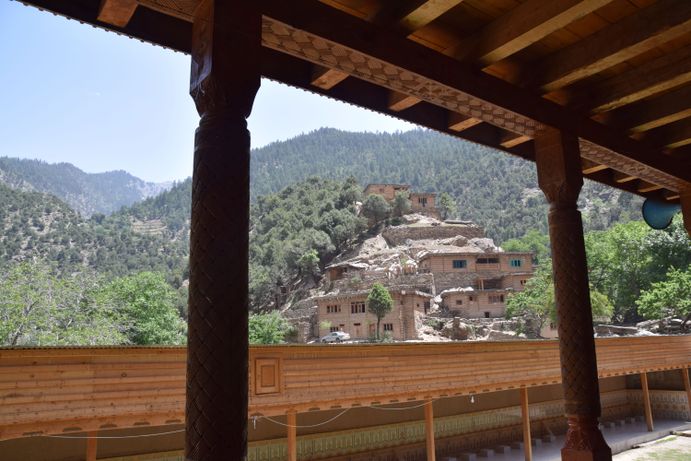

The main village of the Saret valley in Kamdesh District, Nuristan Province, Afghanistan (Franz J. Marty, 16th of May 2022)

For example, in January 2019, an editorial published on the Taliban’s official website explained why democracy is unacceptable, pointing out that «in a democratic system, the biggest fault that exists is deferring to the majority of people’s votes without making a difference between the righteous and the wicked, scholars and ignorants, the educated and the uninformed.»[1] This thought was more recently again repeated by the Taliban’s Chief Justice Abdul Hakim Haqqani in his latest book ‘The Islamic Emirate And Its System’ (‘الإمارة الإسلامية ونظامها’) which was published this year. In this book, Abdul Hakim Haqqani further asserted that candidates in elections would deliberately deceive voters and bribe and that elections are in general susceptible to fraud, create disunity, and are a waste of money (for relevant excerpts and translations of the referenced book, see here).

The above is — as far as it can be determined — in line with the movement’s apparent general stance on and their actions in the selection of their own leaders. Specifically, the Taliban favour (s)elections through what Islamic jurisprudence refers to as the ‘people who lose and bind’ (أهل الحل والعقد ahl al-hall wa’l-ʿaqd), i.e. a special group of people eligible to vote. Who exactly these ‘people who lose and bind’ are is ambiguous and, historically, varied according to time and place (for more details, see this report). What is clear though is that it is contradictory to general suffrage, as is more or less applied in Nuristani council elections.

Making & Enforcing Laws

Another main point of criticism against democracy raised by the Taliban is the existence of man-made laws that can be subject to change as they deem this incompatible with their belief of an immutable divine law (see the above-cited editorial). Such a view does not take into account that Islamic laws do, although they are indeed very detailed, not regulate everything that might arise — meaning that, in certain instances, Islamic law offers no clear solution and the latter has to be found elsewhere (for more details on this, see this already above-referenced report).

Local councils in Kamdesh find such solutions. «Anything that is not regulated by sharia [Islamic law], the council decides on», an old man in Kamdesh’s main village explained. In some instances, councils do this ad hoc and in others they enact general laws. As an example, people from various places in Kamdesh mentioned that councils enact edicts stipulating an obligation for everyone to move their livestock to alpine pastures during summer. If people do not adhere to this, the council enforces often hefty fines in money or in kind that are, each year, adjusted. «Livestock would damage or destroy the scarcely available land in our valleys; that’s why we have to enforce that livestock is moved to high pastures in the mountains in summer», Abdul Qahar explained the underlying reason for such laws. Another example for locally made laws are rules on when wild-growing fruits are allowed to be picked and fines for contraventions thereof.

Punishments for infringements of local laws are often enforced through a gathering of council members and local people whereas such gatherings also resolve other disputes. In some places like the Saret valley, locals also elect specific men to enforce the law. «They are called ‘commandoon’ and are like policemen», Abdul Qahar stated in this regard. However, later explanations made clear that they rather act as mediators and conveners of the aforementioned gatherings than actual policemen. «Such ‘policemen’ are a traditional institution and are called ‘ura’ in the local Kâmviri language», Mr. Strand confirmed to SIGA.

Abdul Qahar, the chairman of the Saret valley council, (in blue tunic and white pakool hat) on the river high up in the Saret valley, Kamdesh District, Nuristan Province, Afghanistan (Franz J. Marty, 16th of May 2022)

That said, while self-governance by local councils in Afghanistan is not unique to Nuristan, the described form of elections with (quasi) general suffrage as well as the enacting and enforcing of general local laws significantly differs from self-governance in other parts of Afghanistan, as a non-Nuristani Afghan who lived several years in Kamdesh confirmed to SIGA.

Taliban Influence?

While in most places in Kamdesh the above-described traditional quasi-democratic self-governance system not only survived but is seemingly still thriving, at least in one valley the Taliban have significantly modified it. The Pitigal valley has a council of 24 members, whereas 12 are selected by their predecessors and are substituted each year while the other 12 members are directly appointed by Sheikh Esmatullah, one of the most influential Taliban commanders in Nuristan who hails from Pitigal and is currently the Taliban’s deputy governor of Nuristan Province. «I have been appointed to the council by Sheikh Esmatullah and act since five years as the chairman», Sediqullah told SIGA in the main village of Pitigal thereby confirming other statements that the members appointed by Esmatullah serve for an unlimited time in the council.

The main village of Pitigal in the valley of the same name in Kamdesh District, Nuristan Province, Afghanistan, as seen from the veranda of the largest mosque in the village (Franz J. Marty, 17th of May 2022)

Asked about this, Mr. Strand termed it a «very un-Nuristani, Islamist system», putting it close to what he called a mullah-dictator system. While Kamdeshis and other Nuristanis had in cases of difficult inter-ethnic negotiations or conflicts in the past reverted to (s)electing a single leader who replaced any elected councils, such absolute leaders traditionally used to be successful herdsmen or other popular civic-minded locals, not mullahs. That mullahs have assumed such more or less dictatorial positions in Kamdesh is only a phenomenon since the clergy of Afghanistan declared jihad (holy war) against the invading Soviet Union in 1979, Mr. Strand elaborated. In this regard, he further added that experience has shown that, if appointed, mullahs have — contrary to herdsmen and other leaders — been mostly reluctant to step down from their extraordinary role, once a crisis was over.

That said, given Esmatullah’s private influence in his home valley as well as the fact that council members in Pitigal stated that their council is neither officially incorporated into the Taliban nor does it get funds or other support from the Taliban Emirate, it is hard to tell to what extent this modification is the work of the Taliban as a government or Esmatullah in his personal capacity. Esmatullah himself was not available for comment and had previously rejected requests to meet with the SIGA fellow.

Be that as it may, all in all and despite the fact that Kamdesh has seen a heavy Taliban presence since well over a decade, the modification of the traditional self-governance system in Pitigal appears to be rather an exception than the rule. As such, the above shows that the Taliban regime, in spite of its overall autocratic and centralised tendencies, leaves room for pragmatic quasi-democratic solutions on local levels. That this is not necessarily new was echoed by Mr. Strand who summarised that «it seems that the Taliban in Kabul are treating Nuristan much like the Afghan king’s regime did in the old days: minimal interference in exchange for compliance.»

Franz J. Marty

[1] From «نظام اسلامی تنھا گزینھء ملت ما», published on 27th of January 2019 on the Taliban website alemarahdari.com which is no longer online; copy in the possession of the SIGA fellow.

Kommentar schreiben