KABUL

December 2020

In a historic agreement signed with the United States of America on 29th of February 2020, the Taliban pledged to prevent any group or individual, including al-Qaida, from using the soil of Afghanistan to threaten the United States of America or its allies. Since then, information gathered on the ground in Afghanistan — some exclusively by the Swiss Institute for Global Affairs (SIGA) — suggests that the Taliban have no intention to break their ties with militant groups with a transnational agenda or to completely curb their activities on Afghan soil, but rather attempt to control them. As it is doubtful to what extent the Taliban want and would be able to effectively control foreign fighters in Afghanistan, this carries the danger that Afghanistan might once again become a safe haven for transnational terrorists.

A still from an al-Qaida-Propagandavideo published in May 2019 showing the flags of the Taliban and al-Qaida to advertise a jointly conducted ambush in Paktika, Afghanistan

The Taliban’s Incorrect Official Denials of the Existence of Foreign Fighters

In July 2020, Zabihullah Mujahid, the official spokesman of the Taliban, told the SIGA fellow in Afghanistan via telephone that the Taliban had already successfully implemented the counter-terrorism guarantees pledged in their agreement with the United States of America. “All our mujahideen [holy warriors] were ordered to not allow anyone to use Afghan soil to threaten other countries and no one will come to harm from [a threat emanating from] here, inshallah. (…) According to our information, there are also no foreign fighters [who could pose a threat to the West] in areas under our control,” he explained.

This, however, stands in stark contrast to official and independent reports as well as the statements of some Taliban fighters on the ground, according to which foreign fighters, including members of UN-designated terrorist organisations such as al-Qaida, remain in Afghanistan. One UN report even claimed in detail that, during 2019 and early 2020, there were several meetings between high-ranking Taliban and al-Qaida members “to discuss cooperation related to operational planning, training and the provision by the Taliban of safe havens for Al-Qaida members inside Afghanistan.”

That foreign Islamist militants are indeed still in Afghanistan was recently proven by the killing of several such individuals. In October 2020, the Egyptian Hussam Abdur-Rauf also known as Abu Mohsin al-Masri was killed in an operation of Afghan government forces in Andar, a district of Ghazni Province, which is located southwest of Kabul; while Hussam Abdur-Rauf was a member of al-Qaida, his exact relationship to this group at the time of his death was not completely clear, with a former high-ranking CIA officer pointing out that Hussam Abdur-Rauf “had somewhat parted ways with [al-Qaida]”. Not long afterwards, on or around 2nd of November 2020, Mohammad Hanif, a man from the Pakistani city of Karachi and a member of al-Qaida’s regional branch (al-Qaida in the Indian Subcontinent) was killed in a raid of Afghan government forces in Bakwa, a district in the western Afghan province of Farah. And on 10th or 11th of November 2020, Aziz Yo’ldosh, an Uzbek national and son of the late Tohir Yo’ldosh, one of the co-founders of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, a UN-designated terror organisation, was killed in Ghormach District in the northern Afghan province of Faryab. While details of the killings of the mentioned foreign militants in Afghanistan and their relations with the Taliban remain scarce, the fact that they have been recently killed in Taliban-controlled areas inside Afghanistan was confirmed to SIGA by various sources; these sources included locals who are not affiliated with the government and, therefore, unlikely to be biased. Moreover, the Taliban — usually fast to denounce reports that might cast a negative light on them as fake enemy propaganda — remained suspiciously silent on the above incidents.

Picture of Egyptian al-Qaida member Hussam Abdur-Rauf after he was killed in an Afghan government operation in Andar, Ghazni Province, Afghanistan, in October 2020 (courtesy of Afghanistan’s National Directorate of Security (NDS))

In view of all this, there is little doubt that official Taliban statements are misrepresenting the situation concerning foreign fighters in Afghanistan which, in turn, raises questions over the Taliban’s seriousness to prevent transnational terrorists from operating in Afghanistan. [1]

The Taliban’s Apparent Internal Policy: Controlling Foreign Fighters

With that said, information gathered during the past months suggests that the Taliban have no intention to distance themselves from foreign fighters, but apparently attempt to control them. For example, on 13th of September 2020, Ehsanullah Ehsan, a former spokesman of the Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and the TTP splinter group Jamaat ul-Ahrar tweeted photographs of two pages of a document in Pashto that was reportedly issued by the Afghan Taliban. [2]

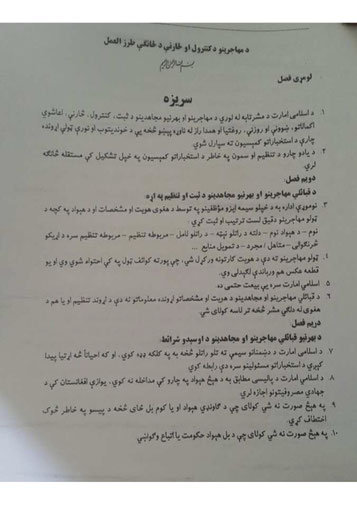

Photos of two pages from an apparent Taliban Document titled "Instructions for Control and Supervision of Refugees"

The document is titled “Instructions for Control and Supervision of Refugees”, whereas the term “refugee” has several meanings: it can mean actual refugees, but is also used by the Taliban to refer to foreign fighters. In any event, the mentioned document is made up of three sections. The first section declares that a special department in the Taliban’s Intelligence Commission will be responsible for “the affairs of registering and controlling tribal refugees [meaning people from the tribal areas of Pakistan] and foreign mujaheddin, [their] supplies, training, and the prevention of unwanted/unpleasant events/accidents.” The second part then stipulates that all “tribal refugees” and “foreign mujaheddin” have to register with and pledge allegiance to the Taliban and that they shall receive identity cards. The third and largest part is titled “Requirements/Conditions for Stay of Refugees and [Foreign] Mujaheddin [in Afghanistan]” and consists of an array of regulations what such refugees and foreign fighters are allowed to do and what not. From the viewpoint of international counter-terrorism efforts, the most notable stipulations in this third section are that::

- “[Refugees and foreign mujaheddin shall] not interfere in the affairs of any country and can only continue jihad in Afghanistan” (Clause 8);

- “Under no circumstances can [refugees and foreign mujaheddin] threaten the government or citizens from another country” (Clause 10); and

- “[Refugees and foreign mujaheddin] will neither allow nor recruit local people or people from foreign countries [into their groups]” (Clause 23). Other provisions in the document qualify Clause 23 at least implicitly by stating under what circumstances fighters who newly arrive in Afghanistan are granted to stay.

With respect to this document, it has to be noted that the source who shared it has a chequered history. In spring 2017, Ehsanullah Ehsan was taken into custody by Pakistani security forces, with different accounts giving different stories of how this happened. According to Pakistani officials, Ehsanullah Ehsan had given himself up, but a spokesman for Jamaat ul-Ahrar claimed that Ehsanullah Ehsan had been apprehended in the Afghan province of Paktika and then been handed over to Pakistani security forces. In any event, in early 2020, Ehsanullah Ehsan reportedly escaped from custody under similarly murky circumstances that could not be verified. In view of all this, Ehsanullah Ehsan is not the most credible source.

However, a former Afghan insurgent who still retains contacts with his erstwhile brothers-in-arms confirmed exclusively to SIGA that the document is genuine. Specifically, the source asserted that he had seen an original copy in the possession of a friend which bore the official stamp of the Taliban. While the aforementioned could not be corroborated by other sources, Andrew Watkins, who covers Afghanistan as a Senior Analyst for the International Crisis Group, told SIGA that the content of the document “resembles reports from as early as February 2019, according to which the Taliban were trying to track foreign fighters and impose regulations on them.”

One such example was also reported by the mentioned former Afghan insurgent. According to him, already in late May or early June 2020 a Taliban delegation went to the remote Kamdesh District in the eastern Afghan Province of Nuristan to inform foreign fighters reportedly affiliated with al-Qaida there about certain conditions to which they have to adhere, if they should want to stay. The most important of these conditions were that foreign fighters have to inform the Taliban about their presence and are barred from conducting operations without the consent of the Taliban.

That the Taliban attempt to control foreign fighters in Afghanistan and impose restrictions on them is anything but new. Indeed, before the overthrow of their regime in the wake of the terror attacks of 11th of September 2001, the Taliban had, in early 2000, issued 13 points to foreign fighters then present in Afghanistan. These 13 points included that foreign fighters had to register with the Taliban and were not allowed to conduct operations without the approval of the Taliban — the exact same points that have resurfaced now. Now, as then, the reason that the Taliban issued such conditions was apparently pressure from states concerned about Afghan soil being used to train transnational terrorists [3]. The mentioned former insurgents also asserted that the Taliban had reissued such conditions several times in the years since the end of their regime in late 2001.

In this regard, it is essential to note that, despite some statements of U.S. officials alleging that the Taliban have to cut ties with transnational terrorist groups such as al-Qaida (statement by U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo), at least the publicly available main text of said agreement does not include such an obligation. Accordingly, the Taliban would — if they should be able to effectively control and prevent foreign fighters from threatening the United States of America or its allies — be in compliance with the main text of the agreement even if they would not completely break with foreign fighters (for the sake of completeness, it has to be mentioned that one article asserts that an obligation to renounce al-Qaida and the self-declare Islamic State is part of a secret annexe to the agreement; this could, however, not be definitively confirmed and remains somewhat questionable [4]).

Doubts about the Taliban’s Seriousness to Control Foreign Fighters

However, there are two main issues with the Taliban’s apparent current attempt to control foreign fighters. The first one is that there are doubts to what extent the Taliban are serious about wanting to effectively prevent transnational jihadists from threatening other countries.

Such doubts derive, amongst others, from the specific contents of some of the conditions that the Taliban are reportedly trying to impose on foreign fighters present in Afghanistan. For example, Clause 21 of the above cited document states that:

“Apart from the flag of the Islamic Emirate [of Afghanistan] [i.e. the Taliban], [refugees and foreign mujaheddin] have to refrain from [raising] other flags in order to prevent suspicions/doubts [problems].”

While the rationale behind this stipulation cannot be ascertained, the most likely explanation seems to be that the Taliban want to ensure plausible deniability, i.e. to prevent that there is clear evidence of a group’s presence in Afghanistan in case the activities of such a group should trigger concerns or complaints from other states or the international community.

Similarly, the above-mentioned former insurgent told SIGA that one of the conditions that the Taliban had given to foreign fighters in Kamdesh in Nuristan was that they are prohibited from using Afghan SIM cards. This can hardly be interpreted otherwise than a Taliban attempt to prevent foreign fighters from leaving evidence in telephone records and to thereby provide plausible deniability.

This suggests that the Taliban are aware of the potential transgressions of foreign fighters in Afghanistan against other states, but instead of placing the emphasis on preventing this or clearly distancing themselves from such fighters or their groups are rather trying to ensure that there will not be any evidence leading back to Afghanistan and themselves.

Questions About the Taliban’s Ability to Control Foreign Fighters

Even if the Taliban should be serious about effectively controlling foreign fighters and preventing them from posing a threat to other nations, the second main issue is that it is questionable whether or to what extent they would be able to do so. This is arguably most clearly shown by the fact that the 13 conditions that the Taliban had issued to foreign fighters in Afghanistan in early 2000, i.e. at the height of their power, did not prevent al-Qaida leaders, who enjoyed asylum in Afghanistan then, from ordering the terror attacks of 11th of September 2001.

With respect to the current situation and as far as SIGA could determine, there is only one potential example in which the Taliban took concrete steps to definitively ensure that foreign fighters in Afghanistan are effectively hold in check. Specifically, an Afghan who requested anonymity told SIGA that, according to local sources, the Taliban had disarmed fighters hailing from Uzbekistan in Ghormach in the northern Afghan province of Faryab. This reportedly also included the recently killed Aziz Yo’ldosh. While SIGA could not confirm this with other sources, an officer of the National Directorate of Security, Afghanistan’s secret police, deemed the reported disarming of Uzbek nationals by the Taliban in Ghormach possible, adding that the local Taliban would oppose intentions of Uzbek militants in Ghormach to directly threaten Uzbekistan or at least intensify operations along the Afghan-Uzbek border.

Alleged photograph of the Uzbek militant leader Aziz Yo’ldosh, date and location unknown

(Source: https://twitter.com/bsarwary/status/1326812974665912320)

How effective the alleged, but not definitively confirmed disarming of fighters hailing from Uzbekistan in Ghormach was, remains unclear. However, the killing of the reportedly disarmed Aziz Yo’ldosh in a Taliban-controlled area — although its perpetrators, exact circumstances, and motives could not be ascertained — makes it arguably even more likely than before that foreign militants would resist being disarmed or otherwise controlled. This in turn raises questions to what extent the Taliban could or would enforce the disarming of foreign fighters or other measures when facing staunch opposition. While Taliban operations defeating groups of the self-declared Islamic State in eastern Afghanistan show that they could implement restrictions with force, it is doubtful that they would choose to do so. This derives from the fact that the Taliban — due to ideological and other reasons — openly fight the self-declared Islamic State, but not other groups and foreign fighters that allied themselves with the Taliban. That said, also the mentioned Afghan source clarified that the Taliban’s behaviour towards foreign fighters in Ghormach and surrounding areas is the exception and not the rule, explaining that the Taliban continue close “brotherly” relations with foreign fighters in other parts of the country. [5]

In general, there also seems to be an inherent logical problem with the apparent current Taliban attempt to prevent foreign fighters from threatening other nations by imposing conditions on them without clearly breaking with them. While some foreign Islamist militants in Afghanistan might just strive to live under an Islamic government of the Taliban in Afghanistan, at the very least a considerable number and more likely most of them have bigger aspirations — be it to establish a transnational caliphate or to overthrow in their views un-Islamic governments in their homelands, for which they openly advocate in propaganda statements. Accordingly, effectively preventing such foreign fighters from posing a threat to other nations would amount to depriving them of their very raison d’être — which makes it unlikely that they would adhere to conditions imposed by the Taliban which would bar them from pursuing the above-mentioned aspirations and, eventually, put them at loggerheads with the Taliban. Ehsanullah Ehsan, the former spokesman of the TTP and Jamaat ul-Ahrar explicitly mentioned this for the example of the TTP whose main goal is to overthrow the Pakistani state in a blog post published on 15th of September 2020. [6]

What a Safe Haven for Islamist Militants in Afghanistan Would Mean

All the above suggests that Afghanistan would likely again become a safe haven for Islamist militants, including such with transnational agendas, in case the Taliban should again come to power in Afghanistan. How much of a threat this would pose to other nations is hard to assess, but is likely at least to some extent exaggerated by pundits (for an example of such an exaggeration and its qualification, see this in-depth study on Uyghur fighters in Badakhshan).

In this context, it should also be kept in mind that while al-Qaida undoubtedly profited from their refuge in Afghanistan in the planning of the attacks of 11th of September 2001, locations outside of Afghanistan played at least an as important role for the facilitation of these attacks (for more details see The 9/11 Commission Report). Furthermore, and maybe even more importantly, in 2001, al-Qaida was able to take advantage from back then lax transnational counter-terrorism efforts, which they could not do anymore now. Finally, given that terrorists with transnational agendas arguably also have safe havens in countries such as Syria, Yemen, and Libya, where there is no large-scale international military presence, it is questionable whether the circumstance that Afghanistan could again become an easier refuge for transnational terrorists would completely change the global threat posed by terrorists.

Nevertheless, a full withdrawal of all international military forces from Afghanistan would likely considerably increase the risk that terrorists with transnational agendas could use Afghan soil to take refuge and/or plot attacks and train fighters. However, as there is — after almost 20 years since the U.S.-led intervention — little if any appetite for an indefinite large-scale international counter-terrorism mission in Afghanistan and current U.S. efforts to co-opt the Taliban to enforce counter-terrorism guarantees are, as explained above and at least in the current form, doubtful to yield success, the question is, how to otherwise mitigate the risks posed by transnational terrorist groups in Afghanistan that are unlikely to be neutralised in the foreseeable future. [7]

One alternative could be to exert more pressure on the Taliban to change their current stance. As military pressure has, over the past almost 20 years, not achieved the aimed for results, this would likely have to be political pressure; for example, to make it clear to the Taliban that they would again become international pariahs, as they had been in the late 1990s, if they should not change their attitude towards foreign fighters. While it cannot be ruled out that the United States of America is at the moment doing this in closed-door talks with the Taliban, the apparent U.S. desire to leave Afghanistan sooner rather than later as well as the number of concessions the United States of America and the international community have already made to the Taliban casts doubt over whether this is the case — which in turn means that the Taliban will likely continue to cooperate with foreign Islamists militants present in Afghanistan.

Franz J. Marty

[1] Parts of this section were already published in more detail in a feature in The Diplomat on 10th of August 2020.

[2] The mentioned tweet is no longer online as the respective Twitter account has been suspended; an electronic copy of the tweet is in the possession of the SIGA fellow in Afghanistan.

[3] For more details on the Taliban’s efforts to control foreign fighters in Afghanistan before the U.S.-led intervention in late 2001 see Anne Stenersen, Al-Qaida in Afghanistan, Chapter 6 Taliban’s Policies toward the Arabs, Section Taliban’s Thirteen Points.

[4] The referred to article was published by The New York Times on 26th of May 2020 and states that “[a]rguably the only clear-cut condition of the February deal, outlined in one of the secret annexes, is that the Taliban must publicly renounce the Islamic State and Al Qaeda before the full troop withdrawal begins.” As the mentioned annexes remain classified, this could neither be verified nor disproved. However, an official U.S. report quoted the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency as stating that the agreement “does not require the Taliban to publicly renounce al-Qaeda.” It would, also in general, seem strange to leave the publicly available counter-terrorism guarantees in the main text of the agreement apparently deliberately vague, but then contradictorily include the alleged obligation for a clear break of the Taliban from the self-declared Islamic State and al-Qaida in a secret annexe. As the cited article asserts that the Taliban would have to “publicly” renounce the self-declared Islamic State and al-Qaida, the potential argumentation that this was included in a classified annexe to not make it public and that the Taliban can renounce such groups in secret in order to limit damage to their jihadist standing, also does not make much sense. Accordingly, it is questionable whether such an obligation exists.

[5] One of several examples indicated by the source was the northeastern province of Badakhshan. The close relationship between the local Taliban and foreign fighters in Badakhshan is also documented by other sources (see for example this in-depth study on Uyghur fighters in Badakhshan) and there is no sign that the Taliban intend to change this.

[6] The referred to blog post is no longer online; an electronic copy of the text is in the possession of the SIGA fellow in Afghanistan.

[7] That terrorist groups such as al-Qaida are realistically assessed to remain in Afghanistan for the foreseeable future was recently acknowledged by a senior U.S. defense official, who said in a briefing on 17th of November 2020 that “al Qaeda has been in Afghanistan for decades, and the reality is we’d be fools to say they’re going to leave tomorrow.”

Kommentar schreiben